Last week of November—we’re into Act III, now! Or maybe, even probably, you’re not that far yet, which is perfectly fine. As long as you’re writing, it’s all good. The book will be done when it’s done.

But if you are into Act III, here are the prompts for that last act.

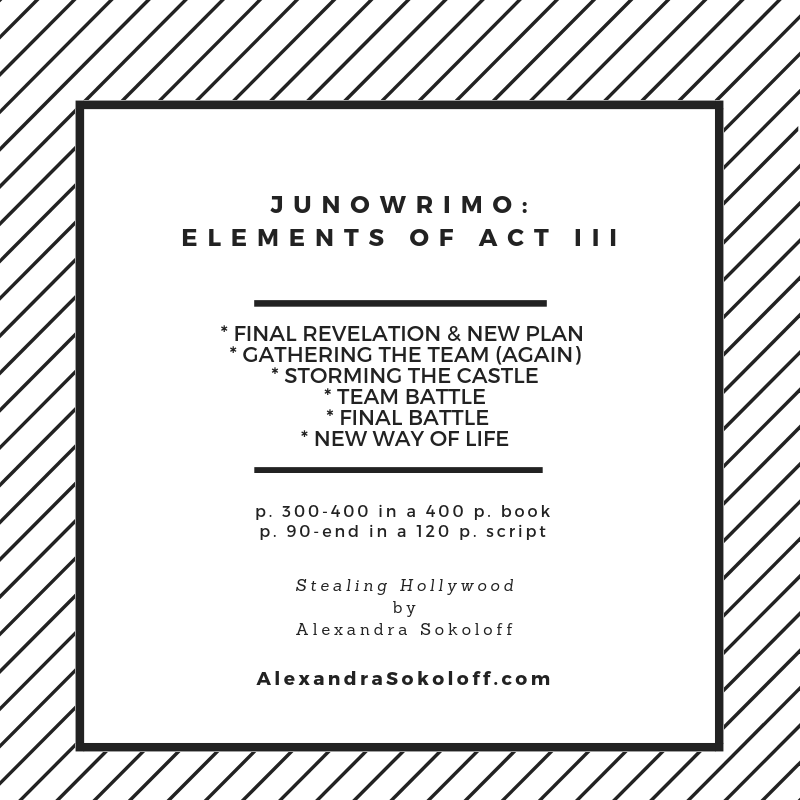

ELEMENTS OF ACT THREE

Act Three is generally the final 20 to 30 minutes in a film, or the last 70 to 100 pages in a 400-page novel. The final quarter, and the shortest quarter.

It is often divided into these two major sequences:

- Getting there (STORMING THE CASTLE)

- The FINAL BATTLE itself

Plus a shorter RESOLUTION — and NEW WAY OF LIFE.

And it usually contains these elements:

- Either here or in the last part of the second act the hero/ine will make a new, FINAL PLAN, based on the new information and revelation of the second act climax.

- There may be a TICKING CLOCK

- The Hero/ine may REASSEMBLE THE TEAM, and there may be another short TRAINING SEQUENCE and/or GATHERING THE TOOLS sequence

- The team often goes in together, first, and there is a big ENSEMBLE BATTLE

- In this battle, we possibly see the ALLY/ALLIES’ CHARACTER CHANGES and/or gaining of desire

- We also get the DEFEAT OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS

- Then the hero/ine goes into the FINAL BATTLE to face the antagonist alone, MANO A MANO

- The final battle takes place in a THEMATIC LOCATION: often a visual and literal representation of the HERO/INE’S GREATEST NIGHTMARE, and is very often a metaphorical CASTLE. Or a real one! It is also often the antagonist’s home turf.

- We see the protagonist’s character arc

- We may see the antagonist’s character arc, too (but often there is none)

- We get a glimpse of the TRUE NATURE OF THE ANTAGONIST

- Possibly there is a huge FINAL REVERSAL or reveal (twist), or even a whole series of payoffs that you’ve been saving (as in Back to the Futureand It’s A Wonderful Life)

- FULL CIRCLE: Not every story uses this, but often the hero/ine returns to a place we saw at the beginning of the story, and we see her or his character growth.

- RESOLUTION: We get a glimpse into the New Way of Life that the hero/ine will be living after this whole ordeal and all s/he’s learned from it

- FINAL BOWS: We need to see all our favorite characters one final time

- CLOSING IMAGE: Which is often a variation of the Opening Image

All right, let’s look at these more closely.

The essence of a third act is the final showdown between protagonist and antagonist.

And sometimes that’s really all there is to it: one final battle between the protagonist and antagonist. In which case some good revelatory twists are probably required!

By the end of the second act, pretty much everything has been set up that we need to know — particularly who the antagonist is, which sometimes we haven’t known, or have been wrong about, until it’s revealed at the second act climax. Of course, sometimes, or maybe often, there is one final reveal about the antagonist that is saved till the very end or nearly the end, as in The Usual Suspects and The Empire Strikes Back and Psycho.

We also very often have gotten a sobering or terrifying glimpse of the TRUE NATURE OF THE ANTAGONIST — a great example of that kind of “nature of the opponent” scene is in Chinatown, in that scene in which Jake is slapping Evelyn and he learns the truth about her father.

There is often a new, FINAL PLAN that the hero/ine makes that takes into account the new information and revelations. As always with a plan, it’s good to spell it out.

There’s a locational aspect to the third act: the final battle will often take place in a completely different setting than the rest of the film or novel. In fact, half of the third act can be, and often is, just getting to the site of the final showdown. One of the most memorable examples of this in movie history is the STORMING THE CASTLEscene in The Wizard of Oz, where, led by an escaped Toto, the Scarecrow, Tin Man and Cowardly Lion scale the cliff, scope out the vast armies of the witch (“Yo Ee O”) and tussle with three stragglers to steal their uniforms and march in through the drawbridge of the castle with the rest of the army (an example of a PLAN BY ALLIES). The Princess Bridealso has a literal Storming the Castle scene, with the Billy Crystal and Carol Kane characters waving our team off shouting, “Have fun storming the castle!”

A sequence like this, and the similar ones inStar Wars and The Empire Strikes Back, can have a lot of the elements we discussed about the first half of the story: a PLAN, ASSEMBLING THE TEAM, ASSEMBLING TOOLS AND DISGUISES, TRAINING OR REHEARSAL.

I’m not just talking about action and fantasy movies, here. You see a truncated version of this team battle plan and storming the castle scene in Notting Hill, when all of Will’s friends pile into the car to help him catch Anna before she leaves.

And of course speed is often a factor — there’s may be a TICKING CLOCK, so our hero/ine has to race to get there in time to – save the innocent victim from the killer, save his or her kidnapped child from the kidnapper, stop the loved one from getting on that plane to Bermuda…

NO. DO NOT WRITE THAT LAST ONE.

Most clichéd film ending ever. Throw in the hero/ine getting stuck in a cab in Manhattan rush hour traffic and you really are risking audiences vomiting in the aisles, or readers, beside their chairs. This is in fact the most despised romantic comedy cliché on every single “Romantic Comedy Clichés” website out there.

But when you think about it, the first two examples are equally clichéd. Sometimes there’s a fine line between clichéd and archetypal. You have to find how to elevate —or deepen — the clichéd to something archetypal.

Even if there’s not a literal castle, almost every story will have a metaphorical Storming the Castle element. The hero/ine usually must infiltrate the antagonist’s hideout, or castle, or lair, and confront the antagonist on his or her own turf, a terrifying and foreign place: think of Buffalo Bill’s basement in Silence of the Lambs,and the basement in Psycho,and the basement/cave in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. The castle can be a dragon’s lair (How to Train Your Dragon), or a dream fortress (Inception), or a church (a million romantic comedies).

Putting the final showdown on the villain’s turf means the villain has home-court advantage. The hero/ine has the extra burden of being a fish out of water in unfamiliar territory (mixing a metaphor to make it painfully clear).

I’ve noticed that in most films, there is a TEAM BATTLE first. The allies get to shine in this one: their strengths and weaknesses are tested, PLANTS are paid off, and allies who have been at each other’s throats for the whole story suddenly reconcile and work together. We also often get the DEFEAT OF SECONDARY OPPONENTS (if we’ve come to hate a secondary opponent, we need to seethem get their comeuppance in a satisfying way — think of Fanny and Lucy Steele cat fighting each other in Sense and Sensibility, and Belloq, General Strasser, and Major Toht’s faces melting in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The TEAM BATTLE is generally a big, noisy SETPIECE scene.

And then, almost always, the hero/ine must go in to the FINAL BATTLE to face the antagonist alone, mano a mano.

So if this is the pattern we see over and over again, how can we possibly make it fresh?

What do I always say? —Look at books and films to see how your favorite storytellers do it.

Silence of the Lambs is a perfect example of elevating the cliché into archetype. The climax takes place in the basement, as it also does in Psycho, and Nightmare on Elm Street. This basement setting is no accident: therapists talk about “basement issues” —which are your worst fears and traumas from childhood — the stuff no one wants to look at, but which we have to look at, and clean out, to be whole.

But Thomas Harris, in the book, and the filmmakers, bringing it to life in the movie, create a basement that is so rich in horrific and revelatory and mythic (really fairy tale) imagery, that we never feel that we’ve seen that scene before. In fact I see new resonances in the set design every time I watch that film… like Mr. Gumb (Buffalo Bill) having a wall of news clippings just exactly like the one in Crawford’s office. That’s a technique that Harris uses that can elevate the clichéd to the archetypal: layering meaning.

But even more than that: Gumb’s basement is Clarice’s GREATEST NIGHTMAREcome to life. Lecter has exposed her deepest trauma, losing the lamb she tried to save from spring slaughter, and now she’s back in that childhood crisis, trying to save Catherine’s life (if you’ll notice, even the visual of Catherine clinging to Mr. Gumb’s fluffy white dog looks very much like a little girl holding a lamb…)

Nightmare on Elm Streettakes that clichéd spooky basement scene and gives it a whole new level, literally: the heroine is dreaming that she is following a suspicious sound down into the basement, and then there’s a door that leads to another basement, under the basement. And if you think bad things happen in the basement, what’s going to happen in a sub-basement?

Comedy characters have a different kind of GREATEST NIGHTMARE.

Suppose you’re writing a farce. I would never dare, myself, but if I did, I would go straight to Fawlty Towersto figure out how to do it (and if you haven’t seen this brilliant TV series of John Cleese’s, I envy you the treat you’re in for). Every story in this series shows the quintessentially British Basil Fawlty go from rigid control to total breakdown of order in the side-splitting climax. It is the vast chasm between Basil’s idea of what his life should be and the chaotic reality that he creates for himself over and over again that will have you screaming with laughter.

Another very technical lesson to take from Fawlty Towers—and from any screwball comedy or farce — is how comedies use speed in climax. Just as in other forms of climax, the action speeds up in the end, to create that exhilaration of being out of control — which is the sensation I most love about a great comedy.

In a romance, the Final Battle is often the hero/ine finally overcoming his or her internal blocks and making a DECLARATION or PROPOSAL to the loved one. And I’ve noticed that a lot of romances do the declaration in a one-two punch, two separate scenes: the recalcitrant lover makes his or her declaration, even does some groveling, apparently to no avail, and only in a later, final scene does the loved one show up with a declaration of his or her own.

An archetypal setting for the Final Battle in romantic comedy is an actual wedding. We’ve seen this scene so often you’d think there’s nothing new you can do with it. But of course a story about love and relationships is likely to end at a wedding.

So again, if you’re writing this kind of story, make your list and look at what great romantic comedies have done to elevate the cliché.

One of my favorite romantic comedies of all time, The Philadelphia Story, uses a classic technique to keep that wedding sequence sparkling: every single one of that large ensemble of characters has her or his own wickedly delightful resolution. Everyone has their moment to shine, and insanely precocious little sister Dinah pretty nearly steals the show (from Katharine Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart, and Cary Grant!!) with her last line: “I did it. I did it all.”

(This is a good lesson for any ensemble story, no matter what genre — all the characters should constantly be competing for the spotlight, just as in any good theater troupe. Make your characters divas and scene-stealers and let them top each other.)

Now, you see a completely different kind of final battle in It’s A Wonderful Life. This is not the classic, “hero confronts villain on villain’s home turf” third act. In fact, Potter is nowhere around in the final confrontation, is he? There’s no showdown, even though we desperately want one.

But the point of that story is that George Bailey has been fighting Potter all along.

There is no big glorious heroic showdown to be had, here, because it’s all the little grueling day-to-day, crazymaking battles that George has had with Potter all his life that have made the difference. And the genius of that film is that it shows in vivid and disturbing detail what would have happened if George had not had that whole lifetime of battles, against Potter and for the town. In the end, even faced with prison, George makes the choice to live to fight another day, and is rewarded with the joy of seeing his town restored.

This is the best example I know of, ever, of a final battle that is thematic — and yet the impact is emotional and visceral. It’s not an intellectual treatise; you livethat ending along with George, but also come away with the sense of what true heroism is.

And the wonderful final battle in The King’s Speech is just Colin Firth facing a microphone and delivering a nine-minute radio broadcast. But we’ve seen him fail this moment because of his speech impediment time and time again in SET UPS; and this time the STAKES couldn’t be higher: it’s his first radio broadcast as King, and he has to convince his already war-weary country to support a war against Hitler.

So when you sit down to craft your own third act, try looking at the great third acts of movies and books that are similar to your own story, and see what those authors and filmmakers did to bring out the thematic depth and emotional impact of their stories (We’ll be doing more of that in the next chapter, too.)

RESOLUTION AND NEW WAY OF LIFE

After the final battle is fought and won, we want to get a sense of the NEW LIFE the hero/ine is going to lead now that they’ve been through this incredible journey.

One of the greatest images of a NEW WAY OF LIFE ever put on film is from Romancing the Stone: the yacht parked in the Manhattan street outside Joan Wilder’s building, and Jack standing on deck waiting for her, with those alligator boots on. It’s a complete PAYOFF of his and her DESIRE lines (and the alligator boots are a great light touch that keeps it all from being too sugary), and a clear indication of what their life is going to be like from now on. Would this have worked as well if that yacht were in a harbor? No way. It’s the extravagance and quirkiness of the gesture that makes it so grandly romantic. It never fails to spike my endorphins, and that’s what these endings are all about.

FULL CIRCLE

Not all stories use this technique, but very, very often at the end of the story the hero/ine returns to the setting of the beginning. And often storytellers use a visual contrast in how that setting appears in the beginning and the end, to show the protagonist’s change in character or attitude.

In the beginning of The Godfather, Don Corleone is in his study, sitting behind his desk in a chair that looks like a throne, holding court and deciding the fates of his supplicants. In the final moments of the story, Michael Corleone stands at that same desk with his subordinates kissing his ring: he has become the Godfather. Early on in Act I of Romancing the Stone,pathologically shy Joan Wilder attempts to leave her apartment and is immediately set upon by street vendors, and we see how incapable she is of handling people and life in general. In Act III, she has returned from her adventure a changed woman, and we see her walking down that same street in her full Kathleen Turner goddesslike radiance, waving off those same street vendors both regally and casually.

You don’t have to use this Full Circle technique, but it can work well to bookend a story and depict CHARACTER ARC. Start to look for it in movies and see how often it’s used! And be aware that these mirroring scenes don’t have to be the very first and very last scenes of the story: often the Full Circle moment comes at the beginning of Act III, or at the start of the Final Battle sequence. This method also works to let an audience or reader know we’re heading into the final stretch, which is always both an exciting and comforting thing for an audience.

Try a little brainstorming of your own.

> Make a Master List of top ten best endings of movies and books, and write down specifically, in detail, what it is about those endings that really does it for you.

> What is your hero/ine’s greatest nightmare? How can you bring that to life in your final battle scene?